“Bad Romance”: How Kaspersky Lab Failed to Conquer the Western Cybersecurity Market

Disclaimer: this article is not sponsored by any third parties and is based solely on public sources. While it includes complimentary statements about the company, these reflect a widely accepted perspective within the security industry. Some technical details have been intentionally omitted as the article is intended for a wide audience. Perhaps there’s at least one reason to read this article if you’re curious about what might happen to a Russia-based hi-tech company that once set out to conquer the Western market…

«We’re only going to be able to solve this [cybersecurity] problem with deep cooperation, between governments and the technology sector.»

Bill Gates

«Surveillance is the business model of the internet»

Bruce Schneier

So, let’s start from the well-known basics and gradually delve into the topic. If any of the links in the text lead to paywalled articles, archive_ph might be an option to access them.

Instead of an introduction here is a brief overview of the company.

Kaspersky (or Kaspersky Lab before rebranding) is a prominent name in the cybersecurity industry, recognized for its innovative anti-malware products and extensive global client base. Its solutions for various platforms and devices consistently meet, and often exceed, industry standards. Founded in 1997 by Eugene Kaspersky, who had been developing antivirus software since the late 1980s, the company has grown into a global leader. Eugene Kaspersky, the company’s co-founder, has served as CEO since 2007, continuing to steer Kaspersky Lab toward new innovations and global expansion.

Basic Terms

Since this article is intended for a wide audience, let’s recall some basic terms.

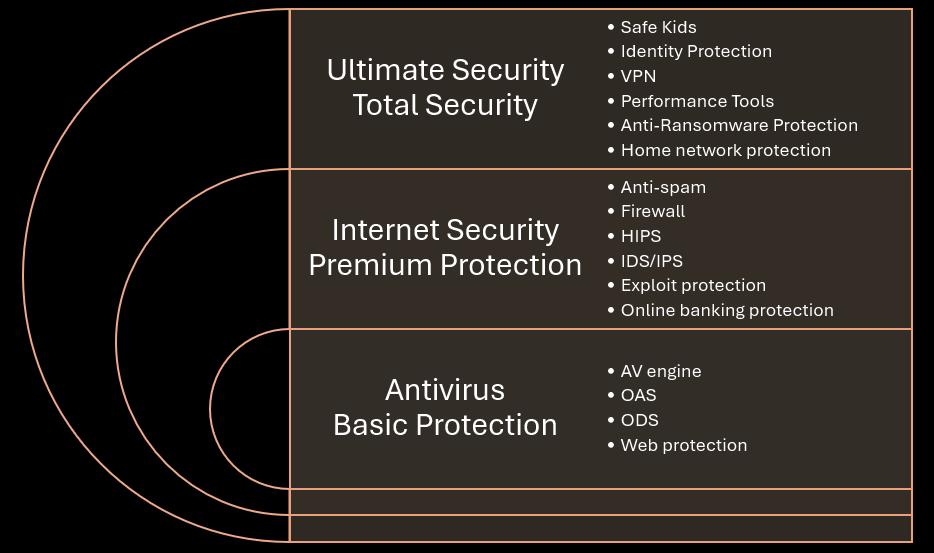

Antivirus (AV) - typically refers to a basic antivirus program that includes core protection features such as an antivirus scanner (on-demand scan, ODS) and a file monitor (on-access scan, OAS). Modern antivirus programs may also incorporate additional modules from more advanced products, like web protection or online banking protection.

Anti-malware product (AM) - a more advanced antivirus program that includes additional security features, which became the gold standard in the 2000s. These features often include web protection, a firewall, anti-spam, Host Intrusion Prevention System (HIPS), Intrusion Detection/Prevention System (IDS/IPS), and anti-ransomware.

Anti-malware solution / Internet Security solution – a security product that includes the widest range of security features inherited from anti-malware products. These solutions often include exploit protection, online-banking protection, VPN, parental control, identity protection, and more, depending on the license.

Endpoint Antivirus / Endpoint Security / Endpoint Protection - a comprehensive antivirus solution designed for corporate workstations. These solutions have the capability for automatic deployment from a central server, requiring no user interaction, and are managed under corporate policies. Typically, this kind of products don’t include protection components found in consumer products, such as a dedicated online banking protection, VPN, parental control, performance optimization features.

In this article, terms like «antivirus», «anti-malware product», and «anti-malware solution» may sometimes be used interchangeably to avoid repetition. However, as mentioned above, they have slightly different meanings. These products are specially designed for Windows, which dominates the anti-malware market. Therefore, the context of this article focuses on the Windows anti-malware products market, the largest segment compared to others.

The Good Old Days

To understand the Kaspersky phenomenon, it’s important to consider the historical context. In the former Soviet Union and early Russia, technical excellence often took priority over marketing. Developing high-quality products required deep technical knowledge but selling them - especially on the global market - was an entirely different challenge. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian companies, including Kaspersky, found themselves with world-class technology but little understanding of how to market it internationally. With no blueprint for success and no prior experience in commercialization, they had to start from scratch to learn how to turn their innovations into profitable products.

Since the early versions of the antivirus, Eugene, a mathematician who gradually became a businessman, placed a strong emphasis on malware detection quality. Throughout the 2000s, Kaspersky consistently outperformed competitors in antivirus tests conducted by the well-regarded Russian test laboratory, Anti-Malware. The company’s solutions achieved top marks in both static and dynamic malware detection, as well as in evaluations of self-protection and anti-rootkit capabilities. As Kaspersky expanded into international markets, the company’s products achieved similar results in anti-malware tests conducted by independent laboratories in Europe.

Branded CD boxes of one of the first versions of the antivirus, source

In the early 2000s, Russia was undergoing a significant transformation, emerging from its Soviet past and embracing new business opportunities, including international recognition. At the same time, Microsoft introduced Windows 2000, the first consumer-friendly version of Windows NT, marking a new era in the evolution of the PC industry. This technological evolution coincided with Kaspersky’s own global expansion, as the company began selling its anti-malware products worldwide.

Windows 2000 was built on Windows NT technology and introduced a revolutionary approach by providing a single OS designed for both enterprise-level servers and personal computers. Both editions shared the same fully x86 kernel, free of the 16-bit legacy code inherent in the Windows 9x family. Powered by the WinNT kernel, it featured a flexible hybrid architecture, offering antivirus vendors the capabilities needed to control the system and manage any potentially installed malware. Developing antiviruses for this platform was much easier than dealing with the 16-bit complexities Windows 9x.

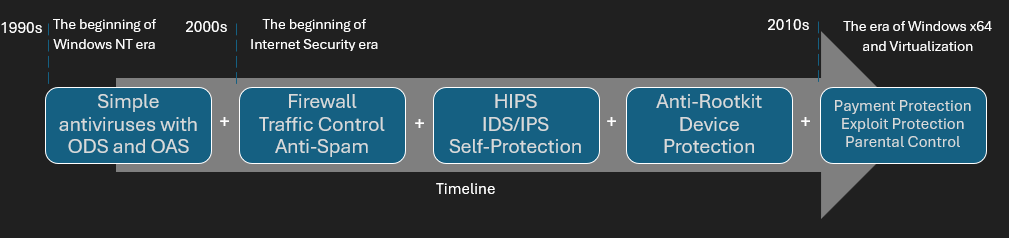

The first decade of the 2000s saw the emergence of nearly all the anti-malware protection technologies that are now standard in modern cybersecurity solutions, including IDS/IPS, HIPS, anti-rootkits, self-protection, firewalls, and application control. These innovations were a response to the rise of new Windows malware with advanced capabilities and rootkit techniques. This period became a golden era for Kaspersky Lab, during which its revenue grew exponentially, as one might expect. Around the mid-2000s, Symantec emerged as the first major player to release an ‘Internet Security’ suite, integrating those security components into a single product - a pivotal moment in the evolution of the industry.

The approximate timeline of antivirus evolution, from basic versions to complex Internet Security solutions

Reaching the peak

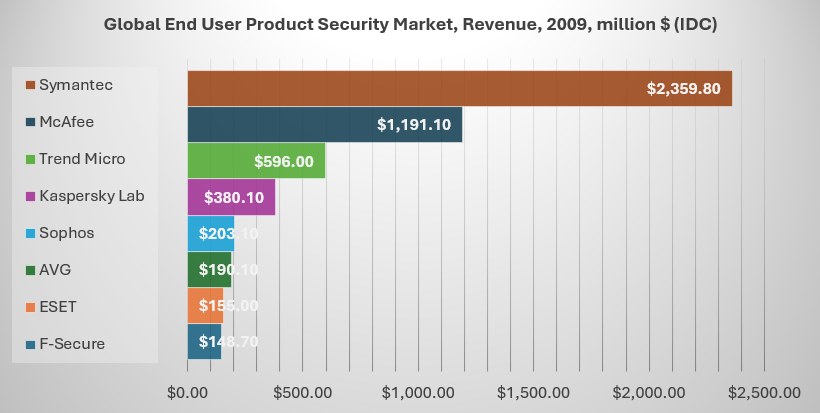

During the first half of 2010s, Kaspersky Lab grew rapidly in the U.S. market, driven by the quality of its malware detection capabilities and its reputation as a leader in cybersecurity research. The company attracted a diverse range of clients, from individual consumers to large enterprises and even some government agencies. By the mid-2010s, Kaspersky had established itself as one of the top antivirus brands in the U.S, alongside native American AV manufacturers such as Symantec, McAfee and Trend Micro. See also Financial indicators of Kaspersky Lab. See also Financial indicators of Kaspersky Lab

On the other hand, the situation began changing starting in the early 2010s, when the company’s rapid revenue growth began to slow. At the time, many companies entered the market offering similar antivirus features, and the lack of new ones contributed to the stagnation of the market. Despite these challenges, Kaspersky continued to successfully promote its products globally, with no major indications of the serious difficulties that lay ahead.

We gained further insights into the company during that period from a 2015 interview with Nikolay Grebennikov, Kaspersky Lab’s former CTO, published by the Russian Forbes. From this article:

Revenue growth slowed at a catastrophic rate - from 40% in 2009 to 6% in 2013, sales were almost not growing. The arrival of the first outside investor (the American fund General Atlantic in 2011 became the owner of 18.7% of Kaspersky Lab shares) resulted in monetary losses, a year later the company bought back its shares. Meanwhile, the plans were ambitious: by the end of 2014, the Laboratory expected to receive revenue of $1 billion (in fact, it was $711 million).

Source: IDC (Worldwide Endpoint Security 2010-2014 Forecast and 2009 Vendor Shares, December 2010)

Meanwhile, Kaspersky’s management was full of optimism about the company’s future and actively pursued new markets abroad. In 2014, the company took a major step by opening an office in Washington, D.C. This move was part of its broader strategy to strengthen its presence in the U.S. and build relationships with government and corporate clients. By 2015, Kaspersky furthered these efforts by hosting its first annual Government Cybersecurity Forum in Washington, D.C., aiming to engage directly with key cybersecurity stakeholders.

“The world’s largest privately held antivirus vendor”

In the second half of the 2000s, it became clear that the company had far more potential than even the founders had anticipated. The question arose: what to do next? According to information obtained by CNews from Eugene’s former spouse Natalya, who was one of the company’s top managers at the time, and an interview with former CTO Nikolay Grebennikov, two opposing views emerged among the management. One group advocated for taking the company public with an eventual IPO, while the other, led by Eugene himself, preferred to keep everything under his direct control.

Natalya and other managers who supported the first viewpoint remained in the minority and were eventually forced to leave the company. Despite the chosen path, Kaspersky made an attempt to sell a share package to the American fund General Atlantic. Both sides did not disclose any details of the deal. What is known is that the attempt was made, but it failed, as Kaspersky was forced to buy the shares back a year later. At that time, General Atlantic was a fund specializing in emerging markets and was seeking opportunities to invest in cybersecurity companies.

As reported by CNews, this move sent a strong signal that the company was preparing for an IPO. After the deal, the fund became the second-largest shareholder after Eugene Kaspersky himself. According to CNews, the shares acquired by the fund previously belonged to Natalya, who sold them after leaving the company. Most of the top managers who were with the company at that time have long since departed. In hindsight, pursuing an IPO on a prominent U.S. stock market could have been disastrous for a Russia-based company in the looming era of severe geopolitical tensions.

Nikolay Grebennikov provided further insights into this period, stating that two distinct camps gradually formed within the company. One consisted of younger technocrats who favored innovation, while the other included older managers from Eugene’s inner circle, who were more skeptical of such changes. Later, the Meduza outlet published a controversial investigation based on insider information about the internal conflicts and power struggles between these two factions, though we will omit the details of that report.

The Top Cyberweapon Intelligence Vendor

In addition to its well-known anti-malware solutions, which account for the majority of its profits, Kaspersky Lab has also established itself as a prolific provider of malware intelligence, particularly in uncovering highly sophisticated cyberweapons linked to state sponsored threat actors (TAs).

A quick glance at sources like Wikipedia or an inquiry to ChatGPT reveals that Kaspersky has played a key role in exposing some of the most advanced state-sponsored malware, including Stuxnet, Flame, Regin, and the tools of the Equation Group. These cyberweapons were developed with considerable financial and human resources, often attributed to government-backed operations. Kaspersky shared detailed analyses of these threats on its dedicated cybersecurity portal, Securelist.

A still from the documentary Zero Days by Alex Gibney. An alleged source within the NSA claims that Stuxnet was developed by the NSA, and the sabotage operation was conducted in collaboration with the CIA and Mossad (Operation Olympic Games). The Russian cybersecurity firm Kaspersky, alongside the Belorussian company VirusBlockAda, was among the first to discover the worm.

Each of these discoveries caused a media frenzy due to the malware’s unprecedented capabilities. For instance, Stuxnet was designed specifically to sabotage Iran’s nuclear enrichment program by targeting uranium centrifuges. Similarly, the Equation Group malware featured an implant that could infect the firmware of hard drives, enabling attackers to control infected systems at a level that was previously thought impossible. This allowed the attackers to bypass conventional detection methods and maintain persistence on compromised machines.

Subsequently, this company’s technical advantage and its distinguished reports on uncovering sophisticated malware became a matter of concern for major U.S. media outlets, which suggested that Kaspersky prioritized exposing U.S.-linked TAs over Russian ones, raising suspicions about the company’s impartiality.

Business in the Post-Soviet Empire

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, relations between Russia and the United States normalized. Many U.S. and European companies entered the Russian market, and in turn, Russian businesses, like Kaspersky, were free to expand internationally. Kaspersky quickly found its place as one of the top antivirus companies in both the U.S. and Europe, competing alongside U.S. cybersecurity giants like Symantec, Trend Micro and McAfee.

However, the stable relations between Russia and Western countries took a significant downturn in 2014, following geopolitical tensions. From that point on, the relationship only deteriorated further. This fact deserves attention, since all subsequent disagreements that could have been resolved were interpreted only in a negative way and ultimately completely destroyed the former friendly relations.

One way or another, the front line of information warfare soon became evident, with companies being labeled based on their country of origin, often without their consent. Increasingly, Western news outlets referenced anonymous ‘government sources’ in reports that heightened tensions. Over time, these reports became a profitable trend - the more they covered the subject, the more they capitalized on the growing atmosphere of mistrust.

These geopolitical tensions inevitably affected businesses on both sides. The escalating distrust began to erode the once profitable communications that had been carefully built. In the high-tech era, operations in cyberspace became particularly vulnerable. As we all know, the absence of Russian companies in Western markets is far less critical for Western economies than the loss of Western companies in the Russian market. In essence, for Western consumers and corporate users, the refusal to use Kaspersky isn’t catastrophic, as there are worthy alternatives available to replace it.

The First Serious Allegations

Starting in the mid-2010s, Western media began publishing allegations about the company’s alleged ties to the Russian government. These claims were attributed to “anonymous U.S. officials” who accused Kaspersky without providing any evidence. Consequently, this information wasn’t taken seriously.

However, in September 2017, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issued a directive prohibiting U.S. federal agencies from using Kaspersky software, mandating its removal within 90 days. The situation escalated in October 2017, when major U.S. media outlets reported that classified NSA data had been found on Kaspersky’s servers. The published reports claimed that over a period of more than two months, classified secret information from the computer of an NSA employee was uploaded to Kaspersky Lab servers. According to Kaspersky’s report, the archive with secret data was downloaded from the computer because the anti-malware product detected one of the Equation Group’s malware files inside it. Equation Group is a notorious TA attributed to the NSA.

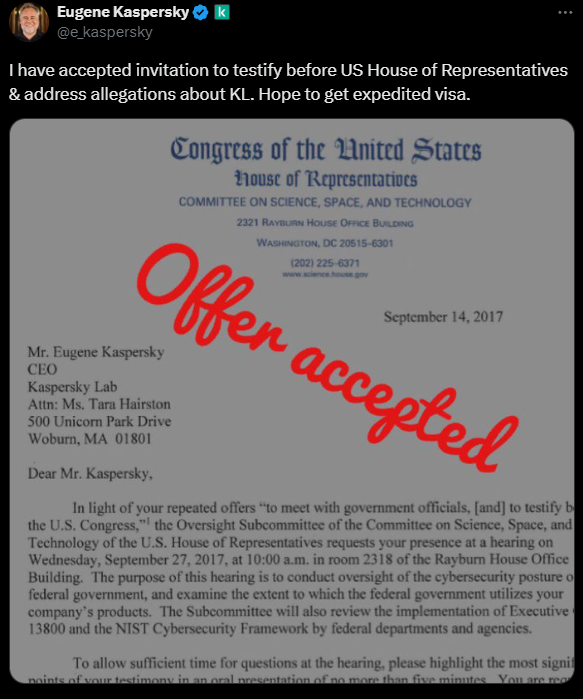

To address the situation, Eugene Kaspersky was invited to testify before the U.S. Congress in September 2017 to answer questions regarding the safety of his company’s products. Both U.S. government officials and private-sector cybersecurity experts were also invited to the session. Initially, Kaspersky accepted the invitation. However, at the last moment, he changed his mind and informed NBC News that he had decided not to travel to the U.S., citing concerns about «unexpected problems» due to the deteriorating relationship between Moscow and Washington.

Eugene’s tweet showcasing the formal invitation from Congress for a hearing in 2017

This story about how U.S. intelligence services became aware of the incident is somewhat murky. According to publicly available information, Israeli state-backed hackers breached Kaspersky’s internal network and discovered the NSA archive on its servers. This revelation sparked concerns that Russian intelligence services had breached Kaspersky’s systems and, using its anti-malware software, gained access to the NSA data. Even more alarmingly, some speculated that this operation was conducted with Kaspersky’s cooperation. Following this narrative, NBC News published an article titled «Russian Hackers Stole NSA Tools From Contractor Who Used Kaspersky Software». Other major U.S. outlets ran similar headlines, citing U.S. intelligence sources. A 2017 New York Times article further elaborated on the situation.

Israeli intelligence officers informed the N.S.A. that in the course of their Kaspersky hack, they uncovered evidence that Russian government hackers were using Kaspersky’s access to aggressively scan for American government classified programs and pulling any findings back to Russian intelligence systems. They provided their N.S.A. counterparts with solid evidence of the Kremlin campaign in the form of screenshots and other documentation, according to the people briefed on the events.

This marked a pivotal moment. Trust in Kaspersky products began to erode significantly, and to mitigate the fallout from the incident, the company launched a «transparency initiative». As part of this effort, Kaspersky opened transparency centers, inviting representatives from businesses and governments to review the antivirus source code and examine how its software was built and updated. However, from my perspective, this initiative was destined to fail from the outset…

Simultaneously, major U.S. retailers BestBuy and Office Depot, following new federal recommendations, pulled Kaspersky products from its shelves. This decision dealt a severe blow to Kaspersky’s consumer segment, as it significantly limited access to its products in one of the largest retail chains in the U.S. Advertising of the company’s products had also been banned on Twitter network.

An open letter to the management of Twitter

Another blow came from the European Union. In a 2018 vote the European Parliament, Kaspersky antivirus was labeled «malicious software». This marked a significant escalation in the scrutiny of Kaspersky’s products. Below is an excerpt from the document detailing this decision.

Calls on the EU to perform a comprehensive review of software, IT and communications equipment and infrastructure used in the institutions in order to exclude potentially dangerous programs and devices, and to ban the ones that have been confirmed as malicious, such as Kaspersky Lab

However, in 2019, the European Commission clarified its position, stating that it was “not in possession of any evidence regarding potential issues related to the use of Kaspersky Lab products.” This statement somewhat mitigated the damage caused by the earlier vote in the European Parliament, though the initial labeling of Kaspersky as «malicious software» had already cast a shadow over the company’s reputation.

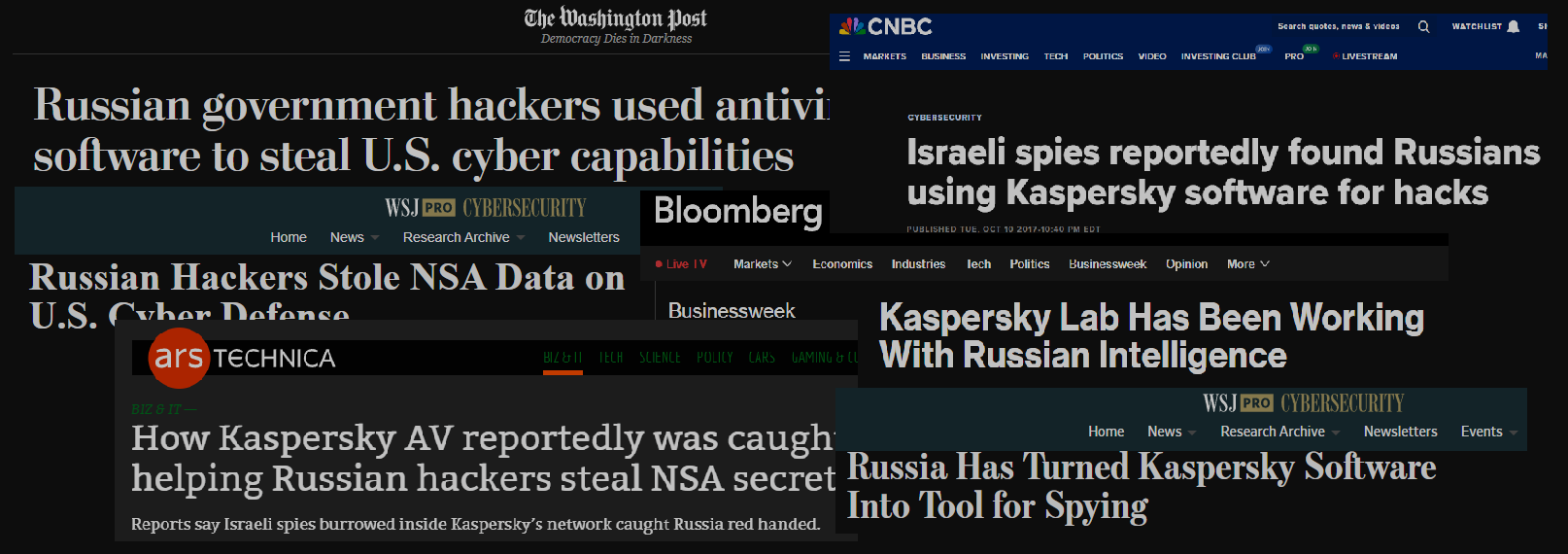

Headlines from major U.S. media outlets, signaling the start of a widespread campaign against Kaspersky, amid allegations of ties to the Russian government

Reasons For Concern

This incident opened up a sensitive debate. Should an antivirus company download an entire archive from a user’s machine if one file inside it is infected, or should it only extract and upload the malware? In Kaspersky’s report, the company admitted that at the time, it downloaded the entire archive, but claimed to have since changed its practices to only extract the infected file. When I discussed this with a friend who works for another leading antivirus company, he was surprised, saying, «Are you kidding? We only upload infected files, not entire archives.»

Setting aside the geopolitical context, it’s important to examine why the U.S. government’s concerns about Kaspersky make sense from a technical perspective. The company’s anti-malware solution, renowned for its ability to eliminate even the most sophisticated threats, requires deep integration into the operating system. Kaspersky’s antivirus operates within privileged Windows services and installs multiple kernel-mode drivers. If compromised, this software could be exploited as a powerful hacking tool with «god mode» capabilities - granting attackers full access to the system. The Department of Homeland Security’s 2017 press release highlighted this very risk, describing how the level of access required by Kaspersky’s software made it a potential target for manipulation.

Kaspersky anti-virus products and solutions provide broad access to files and elevated privileges on the computers on which the software is installed, which can be exploited by malicious cyber actors to compromise those information systems.

Unfortunately, unlike American antivirus vendors, Kaspersky operates under a different geopolitical lens, which has caused its capabilities to be viewed in a negative context.

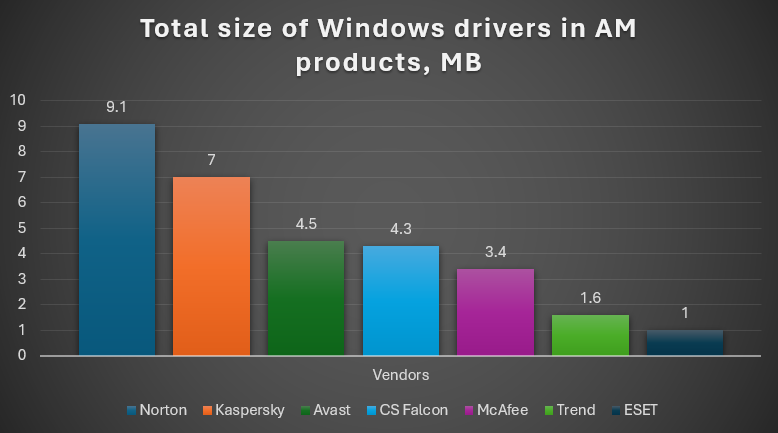

As shown in this data, all leading anti-malware products deploy highly-privileged code to perform their core security functions on systems

It’s worth noting that all leading anti-malware solutions have the same technical architecture as Kaspersky, including highly privileged services and kernel mode drivers. But these solutions don’t belong to the vendors with Russian origins. If you would like to learn more, you can read my earlier study on how much kernel mode code antivirus vendors deploy in the system. It was written after the global outage caused by the buggy driver of CrowdStrike Falcon EDR. Above is an image demonstrating these statistics.

“We Don’t Need Russians On Our Computers”

After February 2022, the relationship between Russia and the U.S., along with European countries, was completely ruined. Since then, the term «good Russian companies» has ceased to exist, especially for those whose products are popular in Russia and used by military or government institutions. Despite significant efforts to establish so-called «transparency centers» in multiple countries, U.S. officials were unimpressed with these initiatives. They subsequently announced new sanctions against Kaspersky, which implied a total ban on the company’s products in the United States.

It’s interesting to note that, according to the Russian business paper Vedomosti, Kaspersky withdrew from a project aimed at creating a secure smartphone for the Russian army. This happened after this geopolitical escalation in February 2022, which was followed by a controversial idea of the company’s PR team to publish a tweet on behalf of Eugene, calling on the parties to reconciliation and «peace throughout the world».

It seems this drastic decision to break such a lucrative deal with the Russian army was an attempt to avoid an impending complete ban from the world’s most profitable market, which was fully recognized by the company’s management. Eventually, Aquarius, the manufacturer of the smartphone, replaced Kaspersky OS with the Russian-made Aurora, a Linux-based mobile operating system developed by Rostelecom for business and government use. In hindsight, this was likely the right choice, as the project would not have remained secret for long anyway.

Nevertheless, the expected sanctions were not imposed immediately. According to the WSJ, this matter initially lacked support within the Biden administration due to concerns that Kaspersky’s antivirus products could be abused by Russian intelligence forces to conduct cyberattacks on American targets. In other words, the administration was not yet prepared to impose such severe restrictions in 2022. Sanctions of this nature typically block or freeze the assets of targeted companies or individuals and prohibit U.S. citizens from engaging in transactions with them. From that article.

The White House’s National Security Council has pressed the Treasury Department to ready the sanctions as part of the broad Western campaign to punish Russia for its invasion of Ukraine, according to officials familiar with the matter. While Treasury officials have been working to prepare the package, sanctions experts within the department have raised concerns over the size and scope of such a move.

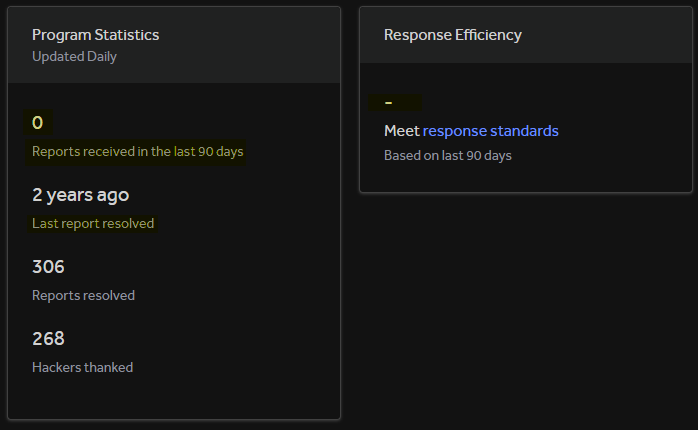

In March 2022, HackerOne, the U.S. based company that is known as a pioneer in managing vulnerability bug bounty programs and responsible disclosure, without any explanation, disabled Kaspersky’s bug bounty program. At that time, I worked as a Kaspersky research developer on this platform dealing with the reproduction accepted vulnerability reports and the communication with security researchers. After disconnection from this platform, the number of valid vulnerability reports significantly decreased and the company lost the opportunity to pay researchers even for already accepted reports.

Statistics from Kaspersky’s Bug Bounty program on HackerOne show that no new reports have been accepted in the past two years

The final point was made in mid-2024, when the United States imposed comprehensive sanctions against Kaspersky and its top managers. These sanctions not only included a total ban on the use of the company’s products within the country but also prohibited delivering updates for already installed products, effectively making their use impossible. Thus, after almost twenty years of Kaspersky’s presence in the US cybersecurity market, the company was expelled. The most profitable market became closed, and the remaining fifty employees in the Boston office became unemployed.

If to look at this situation impartially, sanctions can only be imposed in exceptional cases that pose a serious threat to national security. The Bureau of Industry and Security outlined four points regarding the company’s products as posing «an unacceptable risk to national security».

- Jurisdiction, control, or direction of the Russian Government

- Access to sensitive U.S. customer information through administrative privileges

- Capability or opportunity to install malicious software and withhold critical updates

- Third-party integration of Kaspersky products

At the moment of the sanctions announcement, Kaspersky was the only Russia-based company, whose products were widely used by Americans, including in the corporate segment. If you don’t trust a country, how can you trust a company operating under its jurisdiction. Isn’t it quite simple. Especially when the software from this company takes full control over the operating system and could potentially be exploited for illegitimate activities.

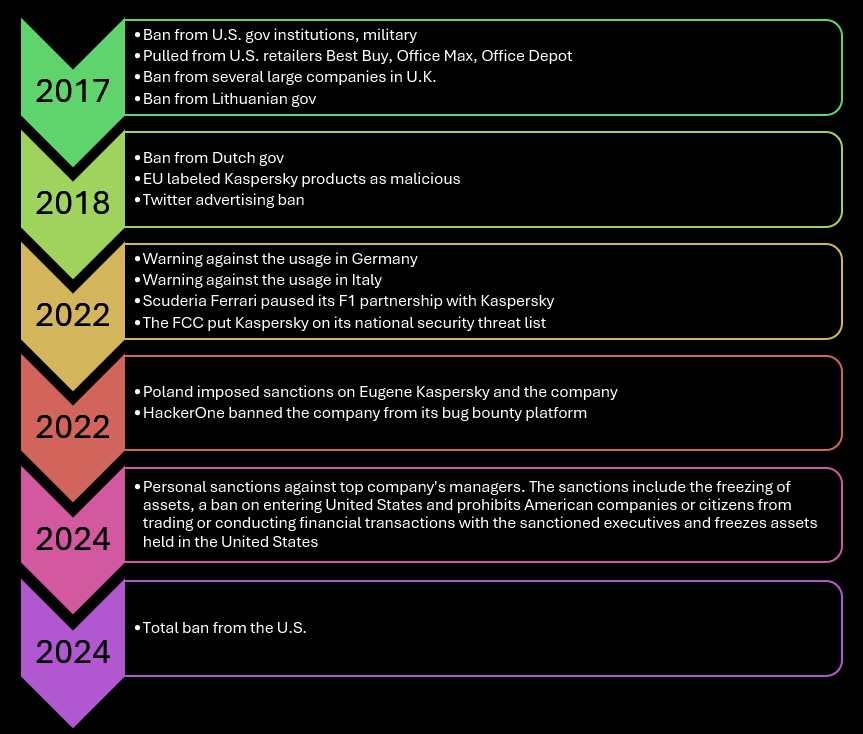

The timeline of the fall

According to Axios, the U.S.-based cybersecurity company Pango acquired all of Kaspersky’s U.S. customers. Pango is known for manufacturing the UltraAV antivirus, as well as other various VPN solutions and identity theft protection tools. There are no other publicly available details about this deal.

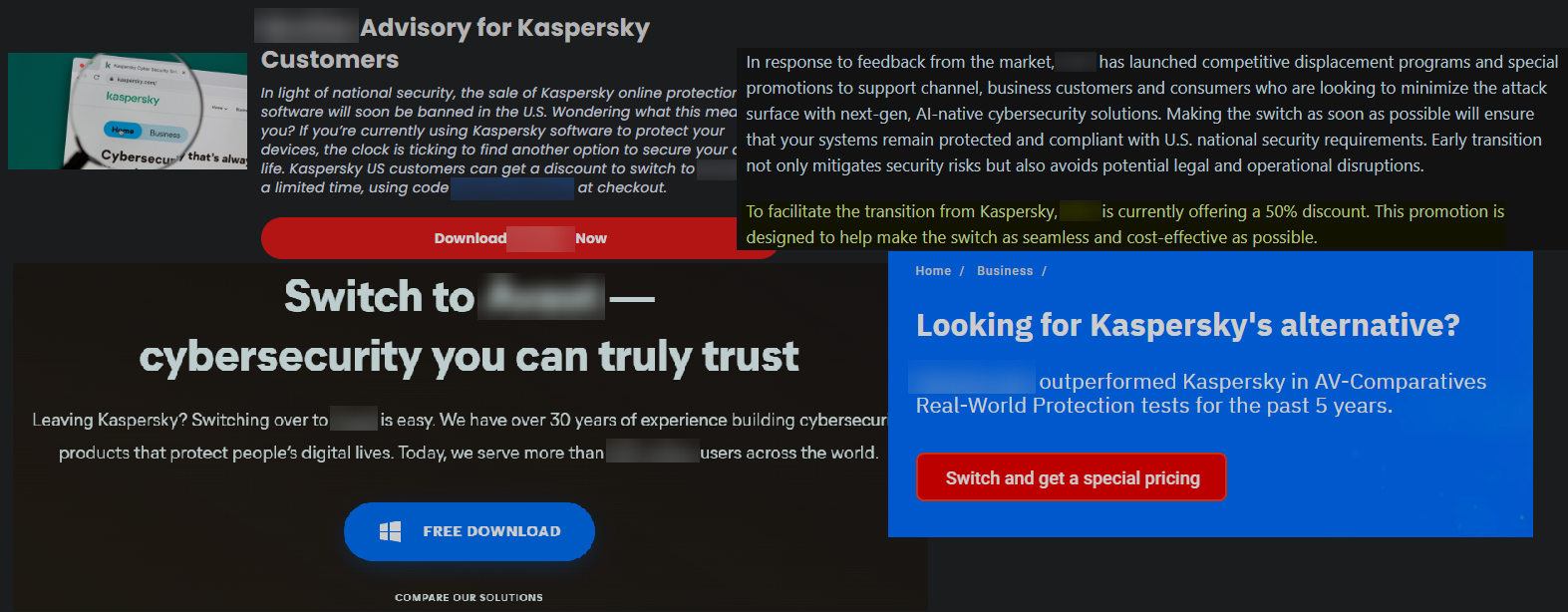

Taking advantage of this situation, several prominent players in the AM market sought to capitalize on Kaspersky’s difficulties by offering discounts for customers looking to replace Kaspersky products with their own. These promotions often included detailed information about the benefits of their solutions, along with instructions on how to remove the now-banned Kaspersky software. By the time of the full ban, Kaspersky’s presence in the U.S. market had likely shrunk to its lowest level since entering two decades prior. Additionally, as far as I know, the first round of sanctions in 2017 also led to the closure of Kaspersky’s U.S.-based anti-malware research division.

The Difficult Road Ahead

According to the aforementioned article featuring an interview with former Kaspersky CTO Nikolay Grebennikov, published by Russian Forbes, Kaspersky’s management believed they would reach $1 billion in revenue by the mid-2010s. However, these very optimistic expectations were not destined to come true. By that time, the market had welcomed other serious Western vendors offering similar security features, and they were unimpressed by Kaspersky’s popularity. Moreover, around the same time, Microsoft began developing its own powerful anti-malware solutions, now known as Defender. Starting as a basic antivirus program released in 2006, Microsoft has since built an anti-malware protection empire catering to all types of users and platforms.

Aside from this, the company faced additional challenges. Newer antivirus products no longer aimed to implement such extensive protection components designed to operate in kernel mode, instead opting for alternative approaches. For instance, many focused on developing standalone tools to target specific sophisticated malware rather than incorporating complex drivers into their anti-malware products. This allowed them to achieve better performance. Additionally, the anti-malware market evolved rapidly, and simply adding new privacy or performance tools to an antivirus bundle was no longer a sufficient strategy. Some manufacturers also began licensing third-party antivirus engines and core components from larger vendors, allowing them to sell their own anti-malware products in local markets, thereby displacing established foreign vendors. Consequently, the market became much more diverse, and companies that couldn’t adapt to these new realities gradually saw their positions weakened.

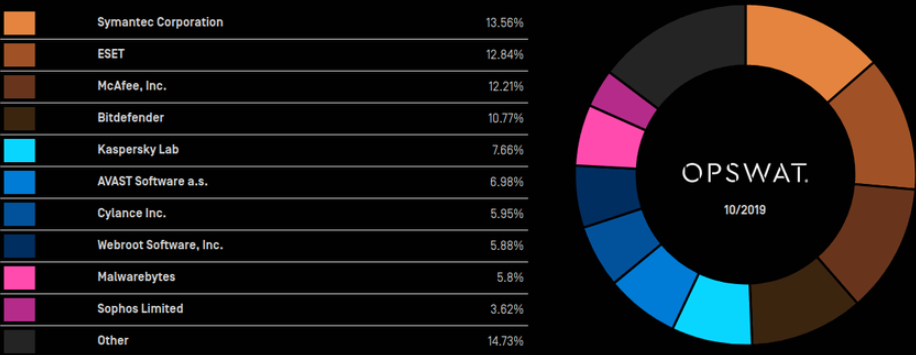

According to a 2019 ranking of the largest antivirus software manufacturers for Windows, published by OPSWAT, ESET made a significant leap, securing second place in the rankings and surpassing even McAfee. Bitdefender and Avast had also significantly strengthened their positions at that time. Based on the latest data, ESET’s revenue from product sales may now significantly exceed that of Kaspersky Lab.

OPSWAT Windows antivirus market share, October 2019

The current geopolitical situation has inadvertently benefited Kaspersky, as all major Western anti-malware vendors have left the Russian market. For instance, ESET, which previously held a solid second position in Russia with a customer base of tens of millions, exited the market. Symantec, which commanded roughly 5% of the market share, ranked third. Avast, aiming for greater market penetration, even opened an office in Moscow in 2017. Nevertheless, the probability of Kaspersky returning to the U.S. market is very low, even in the long term, as restoring credibility between countries may take decades, and sanctions are rarely lifted except in exceptional cases.

When I worked at Kaspersky (left the company a year ago), there were unconfirmed rumors that relocating the company HQ to a new location was being considered. Assume that a new location could be in Europe or the United States. However, in today’s reality, this option seems entirely unrealistic, even if such a decision was being considered.

We’ve seen a similar scenario with Group-IB, another well-known Russian cybersecurity company that focuses on investigating of cybersecurity incidents and assisting in recovery efforts. After the arrest of its CEO, Ilya Sachkov, on treason charges, the company split into two, severing all ties between them. One part, under a different name, continued to operate in Russia, while the other retained the original name and relocated to Singapore.

Will see what happens next… According to various publications, Kaspersky has been investing significant resources into the development of its brand operating system, KOS, which is reportedly capable of running on a range of devices, including computers, smartphones, and industrial systems. Nevertheless, Windows-based AM products remain the primary revenue stream for any vendor in the market. Retaining its existing customer base seems to be one of Kaspersky’s main priorities moving forward.